Clifford Harper

Clifford Harper (Chiswick, Londra, 13 luglio 1949 ) E' un artista e illustratore anarchico britannico.Biografia

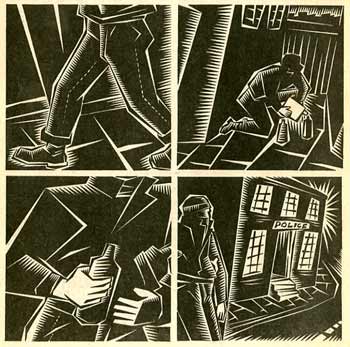

Figlio di un postino e di una cuoca, Clifofrd Harper inizia a lavorare all'età di 14 anni essendo stato espulso da scuola l'anno precedente. Di carattere ribelle, per un certo periodo vive in una comune di Cumberland, ma durante gli anni settanta si lega alle attività del movimento squat di Londra.Essendo dotato di una naturale vocazione artistica, da autodidatta apprende l'arte dell'illustratore, riuscendo a conciliare questa nuova passione con l'impegno sociale che lo porterà a realizzare diversi disegni che andranno ad illustrare le pagine della stampa radicale inglese e internazionale. Grazie all'influenza esercitata da disegnatori come Eric Gill, Félix Vallotton e Frans Masereel, Clifford Harper nel 1974 pubblica un'antologia di manifesti e disegni Radical Technologie, in cui vengono illustrate una serie di visioni utopiche post-rivoluzionarie incentrate su temi come l'autosufficienza, l'autonomia e la tecnologia alternativa in contesti urbani e rurali

Nel 1978 pubblica il libro Class Comix War, mentre nel 1984 e nel 1987 è la volta rispettivamente di The Education Of Desire ed Anarchy, a Graphic Guide. Lavora anche per l'organizzazione dell' Anarchist Bookfair, Fiera del Libro Anarchico, mostra annuale del libro anarchico.

Ha creato una sua piccola casa di produzione denominata agraphia press, che ha contribuito a farlo notare per la qualità del suo lavoro. Questo gli ha permesso di collaborare anche per la stampa nazionale, soprattutto per The Guardian, e pubblicherà nel 2003 una antologia di disegni già editi: Country Diary. Pubblica poi Visions of Poesy - an Anthology of Anarchist Poetry a cura di Dennis Gould e edito da Freedom Press nel 1990. Una mostra di suoi disegni Graphic Anarchy si è tenuta alla Newsroom Gallery di Londra nel mese di aprile e maggio 2003.

Nel mese di aprile del 2006, viene colpito da un attacco di cuore, ma è riuscito a superare questa crisi.

Bibliografia

- Radical Technology - includee 6 'Visiones' e altre opere di Clifford Harper (editato da Peter Harper, Godfrey Boyle e dagli editori di Undercurrents Wildwood House, 1976)

- The Education Of Desire - The Anarchist Graphics Of Clifford Harper (Annares Press, 1984)

- Anarchy, A Graphic Guide (Camden Press, 1987)

- The Unknown Deserter - the Brief war of Private Aby Harris in Nine Drawings (Working Press, 1989)

- An Alphabet (Working Press, 1989)

- Visions of Poesy - an Anthology of Anarchist Poetry (coeditato con Dennis Gould, Freedom Press, 1990)

- Country Diary (Agraphia Press, 2003)

Clifford Harper is a worker, illustrator and militant anarchist. He was born in Chiswick, West London - at that time within Middlesex - on 13 July 1949. His father was a postman and his mother a cook. Expelled from school at 13 and placed on 2 years probation at 14, he then worked in a series of "menial jobs" before 'turning on, tuning in and dropping out' in 1967. After living in a commune in Cumberland, he started a commune on Eel Pie Island in the River Thames near Richmond, Surrey, in 1969. In 1971 he took part in the All London Squatters organization, squatting in Camden, North London, then Stepney Green, East London, and Peckham in South East London, while being very active in anarchist circles. In 1978 he settled in Camberwell where he has lived ever since.He has suffered from poor health for most of his adult life. After contracting TB in France in 1969 Harper was hospitalised for 3 months in 1971, leaving his lungs and heart badly damaged and leading to heart failure in 2002. In early 2006 he survived heart attacks, in 2008 was diagnosed as diabetic, further heart attacks followed and other health problems continue.

Beginning in the early 1970s he became a prolific illustrator for many anarchist, radical, alternative and mainstream publications, organisations, groups and individuals including Freedom Press, Undercurrents, Respect for Animals, BIT Newsletter, Arts Lab Newsletter, Idiot International, 1977 Firemans Strike, Libertarian Education, The Idler, Radical Community Medicine, Anarchy Magazine, Black Flag, Anarchy Comix, Common Ground, Industrial Worker, Aberlour Distillery, Country Life, Graphical Paper and Media Union, The Times Saturday Review, Tolpuddle Martyrs Festival, New Scientist, Oxford University Press, Penguin Books, Times Educational Supplement, London Anarchist Bookfair, Public and Commercial Services Union, The Sunday Times Magazine, Catholic Worker, Soil Association, The Bodleian Library, New Statesman, Cienfeugos Anarchist Review, Headline Books, The Financial Times, Resurgence, Scotland on Sunday, Town and Country Planning Association, Movement Against A Monarchy, Nursing Times, John Hegarty, The Listener, Zero, McCallan Whisky, Solidarity, New Society, News from Neasden, House & Garden, The Tablet, Radical Science Journal, Royal Mail, The Co-ops Fairs, Picador Books, Pluto Press, Working Press, Anarchismo, Insurrection, Our Generation, Ogilvy & Mather, Vogue, Radio Times, National Union of Teachers, Faber & Faber, Pimlico, Trades Union Congress, Transport and General Workers Union, Serpents Tale, Compendium Books, Poison Girls, Yale University Press, Verso, The Daily Telegraph, The Independent, Elephant Editions, Intelligent Life, Landworker, Zounds, Honey, New Musical Express, Knockabout Comics, Trickett and Webb, The Times, See Sharp Press, Countryside Commission, Industrial Common Ownership Movement, BBC Worldwide, Stop the War Coalition, Aganovich, The Folio Society, Unison, Unite the Union, Anarchist Studies, Country Standard,Strike, Fitzrovia News, Anarchist Black Cross and many others. In 1992 he won a W H Smith Illustration Award and in 2002 he was the winner of the Trade Union Press and PR Award for Best Illustration.

His early drawing style was typically exemplified by the utopian 'Visions' series of posters, for the Undercurrents 1974 anthology Radical Technology. These were highly detailed and precise illustrations showing scenes of post-revolutionary self-sufficiency, autonomy and alternative technology in urban and rural settings, becoming almost de rigueur on the kitchen wall of any self-respecting radical's commune, squat or bedsit during the 1970s. Of these posters Harper writes:

Funnily enough they were particularly popular in Spain following the death of Franco and the liberalisation that followed that happy, but long overdue, event. I think the reason for their success is that although they are utopian images they depict an existence that is immediately approachable—all it would take is the seizing of a few empty buildings and the knocking down of a few meaningless walls...Heavily influenced by George Grosz, Félix Vallotton, Fernand Léger, Eric Gill and, most of all, the narrative woodcuts of Frans Masereel, Harper's style evolved in the 1980s in a bolder, expressionist direction, with much of his later work resembling woodcut, although he mainly works in pen and ink, and watercolour.

In 1987 Anarchy, A Graphic Guide, which Harper wrote and illustrated, was published by Camden Press:

Like all really good ideas, Anarchy is pretty simple when you get down to it - Human beings are at their very best when they are living free of authority, deciding things among themselves rather than being ordered about. That's what 'Anarchy' means - Without Government.This has become a definitive and popular introduction to the subject, combining a thorough and inclusive overview of anarchism with his distinctive illustration. England's principal radical illustrator, he had a strong association with Freedom Press from 1969 up to 2005 as well as many other anarchist groups, publications and individuals. Harper remains a "100% committed" and engaged anarchist activist, having been deeply involved with organising the UK's annual Anarchist Bookfair, re-designing Freedom newspaper in 2005, producing books, pamphlets, posters, book covers, postcards and drawings for, and supporting, anarchists everywhere. His drawings have been used and reproduced by anarchists and others in nearly every country of the world. He has produced a book of anarchist postage stamps 'For after the Revolution' and created his own small publishing project Agraphia Press. He does a great deal of work for the Union movement in Britain and he began working for The Guardian in the early 1990s, his work appearing every week until he was sacked in 2014. His illustrations for The Guardian's Country Diary column were published as a book in 2003 by Agraphia Press. Graphic Anarchy, an exhibition of his work, was held in 2003 at the Newsroom Gallery, London. He is currently writing and illustrating an entirely new version of his book Anarchy: A Graphic Guide. You can see some of the new drawings at www.facebook.com/AnarchyAGraphicGuide. Although in poor health, Harper continues to work as an illustrator. One of his drawings, 'Solidarity', was displayed on a giant screen in Cairo's Tahrir Square in 2011.

Books by Clifford Harper

- Class War Comix - New Times (Epic, 1974 & Last Gasp, 1979)

- Radical Technology - includes 6 'Visions' and other drawings by Clifford Harper (edited by Peter Harper, Godfrey Boyle and the editors of Undercurrents, Wildwood House, 1976)

- The Education of Desire - The Anarchist Graphics of Clifford Harper (Annares Press, 1984)

- Anarchy, A Graphic Guide to the History of Anarchism (Camden Press, 1987)

- The Unknown Deserter - the Brief War of Private Aby Harris in Nine Drawings an A6 chapbook (Working Press, 1989)

- An Alphabet an A6 chapbook (Working Press, 1989)

- Anarchists: Thirty Six Picture Cards (Freedom Press,1994)

- Prologemena to a Study of the Return of the Repressed in History (Rebel Press, 1994)

- Visions of Poesy - an Anthology of Anarchist Poetry (co-edited with Dennis Gould and Jeff Cloves, Freedom Press, 1994)

- Stamps: Anarchist Postage Stamps for after the Revolution (Rebel Press, 1997)

- Philosopher Footballers: Sporting Heroes of Intellectual Distinction (Philosophy Football, 1997)

- The Guardian Country Diary Drawings (Agraphia Press, 2003)

- The Ballad of Robin Hood and the Deer (Agraphia Press, 2003)

- The Ballad of Santo Caserio (Agraphia Press, 2003)

Interviews > Clifford Harper

Chances are you’ve seen Clifford Harper’s artwork hundreds of times before and never realised who it was making these incredible illustrations. At least that was how I discovered him, zines, gig fliers, posters, books; all seemed to have similar illustrations, but never a credit of who actually created them. Eventually I found out Clifford Harper’s name and was able to properly discover his illustrations. He makes amazing black and white pieces of work, with intricate lines and wonderful characters. They’re pieces of the city, countryside, and everyday people going about everyday things; as well of course as all the artwork specifically drawn to celebrate, and agitate for, anarchy. He has been working – seemingly nonstop – since the 1970s and has produced a wealth of work, predominantly in black and white, and exploring the world as he sees it. Clifford was kind enough to take some time to answer a few questions I had for him in September 2007, and those are what follows.

LH: You recently had a really serious health problem – I’m glad you’re working again – but I was wondering whether it had had any effect on your politics or artwork? Sometimes its the cue for people to ‘find god’.

Clifford Harper: Thanks. The effects are pretty straightforward. Some of the medication makes it difficult to be ‘creative’ as it slows and dulls the mind quite a bit and causes overwhelming tiredness. And from time to time I go through periods of agonising pain, which takes over everything else. This all means I’m working less, so earning lower wages, so I’m ill and poor. Not a pleasant place to visit.

As to ‘politics’, well, my love of the NHS is stronger and deeper, and my hatred of it’s enemies as strong. The ever present chance of suddenly dying makes me angry and I worry a lot about not getting important stuff finished. But my anarchism is as real as ever. As for ‘god’, there’s no such thing. It’s just an ugly story peddled by con-artists. Take my word for it.

LH: How did you get interested in anarchy?

CH: It got interested in me, I think. I first heard the word at 14 (1963). I was hooked straight away and never looked back, but I was a little rebel and trouble maker for as long as I can remember. I was expelled at 13 and on 2 years probation at 14. My mum instilled in me a thorough scepticism of the current set-up and its ‘values’. As a working class teenager in the early ’60’s I regarded the middle-class world as something that simply must go, (I still do), and anarchy as it’s natural and one and only replacement.

LH: Why did you start getting involved in making art? Do you think it’s important for ideas to be represented graphically?

CH: What other way is there? For the vast majority of humanity pictures have always been the method of communicating and holding onto ideas, besides speech and song. Historically only a handful of people can read and write, but writers and their words dominate. If you can’t read or write you’re sub-standard. That’s just more middle-class bollocks. Everyone can make pictures.

LH: You’re a self-taught artist ? do you think that’s been important to how your style has developed?

CH: I don’t have a style. I use many different styles, whichever works best for the subject I’m drawing, or the place it’ll be published, or what I’m asked to do. This ’self-taught’ thing, I dunno how real that is, or how important. I think everyone is ’self-taught’, whatever they do, but we’re ‘taught’ that self-knowledge, practice and experience is less valid than what we’re ‘taught’. If you see what I mean. Just another way to make us, and our abilities, seem worthless and small.

Maybe for me being ’self-taught’ keeps my mind open. The process of working out what to draw and how to draw it requires that I keep looking around, keeping my eyes wide open.

LH: If you could have would you have liked to have gone to art school or was the education you gained in work more useful?

CH: I could have gone to art school, but in ‘68 there were much more interesting things to be doing – none of them in a college. Besides, when I was a schoolkid I spent most of my time truanting, I couldn’t abide school, it was both a prison and an absolute waste of my time, so the idea of signing up to another bout of mis-education was a poor joke. All the students I met had dropped out, which told me something. I was an apprentice in a print works and then a design studio, in those places I picked up an excellent knowledge of materials and methods, particularly origination for offset litho printing – (making artwork).

LH: Has it been possibly to survive on creating art, or have there times when it’s been a struggle. Have you always worked principally as an artist, or have you had to take jobs on the side?

CH: Yes, it’s the only way I earn my living as it’s the only skill I have. I don’t create ‘art’, by the way. I’m not an ‘artist’, I’m an illustrator, a craftsman. It’s always been a struggle, I don’t earn much money, I’m not interested in that particularly, but being free of the chasing money thing allows me to do other things that interest me much more.

LH: Has being an anarchist – and a vocal advocate for anarchy – ever hindered you in terms of getting work, or having the opportunity to display work in places?

CH: Absolutely not. The people I work for, mainly commissioning editors and designers, are on the whole quite sympathetic to anarchist ideas, (like a lot of people), so there’s never a problem. I guess there are times when someone doesn’t want to be associated with an anarchist. That’s fine by me. My work is displayed all the time, on hundreds of thousands pages.

LH: Many, if not most, people within the anarchist/ anti-authoritarian movement are either suspicious or hostile to the mainstream media. What are your thoughts on it?

CH: I think they’re right. I agree with them. All the anarchists I’ve met who work in ‘the media’ feel the same way.

LH: Would you rather be able to just work for radical publications/ projects or do you enjoy the challenge of producing art for such a large audience?

CH: I’ve worked for most anarchist publications over the last 40 years. I’ve also worked for every national newspaper, except the Mirror and Sun – they don’t use illustration. When it comes to drawing for large numbers of people – well, it answers itself, don’t you think?

LH: The majority of your work is black and white. What is it that appeals to you about monochrome? Or is it because life is black & white?

CH: That’s a nice question. It’s black and white, or B/W as we say in the trade, because that’s what I learned to do first, so I kind of got stuck with it. But as I studied the work of earlier anarchist illustrators, such as Frans Masereel or Felix Valloton, who also made B/W images, I got very caught up in this question of restrictions – the chains that bind us. It’s complicated, but one aspect of it is similar to the question of wealth. A lot of the art that appears today is strongly married to wealth, not just in the obvious way -the rich pay for the artists greed – but the work itself is ostentatious and arrogant, artists trample all over the feelings and hearts of people. For what? For their Art. Screw that. A portrait of Myra Hindley! No apologies, just “This is Art. I am an Artist. You cannot understand. You’re ignorant peasants.” They’re like 18th century aristocrats – in more ways than one.

B/W illustration isn’t like that. It’s sort of poor. I like that about it.

When I was a lot younger I did see things pretty much black and white, it’s true. And my work was connected to that. I still think the essentials are black and white. But why I like drawing B/W is the challenge, it’s much more fun, much more difficult, and when I produce a really good drawing it’s much more of an accomplishment.

LH: Do ever feel alienated from the anarchist movement ? Have you found it difficult to remain engaged after all your years of involvement?

You bet.

LH: What do you hope people take away after looking at your artwork?

CH: Pleasure

LH: Whilst there aren’t, to my knowledge at any rate, many people in the UK producing artwork similar to yours there are quite a few in the USA, such as Eric Drooker, Seth Tobocman and Peter Kuper (all of whom are involved in World War 3 Illustrated). Have you ever had any contact with them, is it important for you to network with other anarchist illustrators/ artists? Do you take inspiration from any contemporary artists?

CH: Not really. Eric Fraser said that an illustrator needs to be like a monk. But I really dig their work, and what Josh MacPhee is doing. Anarchist creativity is absolutely on the up, no doubt about it. Which is fucking fantastic. And I’m glad to be part of it, let me tell you.

LH: Aesthetically nowadays anarchy is often associated with cut ‘n’ paste and quite rough, fast artwork, with only limited craft involved. Your artwork obviously has a lot of craft, with a lot of intricacy and detail. Do you feel any tension there? Do you think that it’s connected to the fact that anarchy is sometimes seen as something that young people with too much energy are involved in?

CH: For me it’s a real drag. I wouldn’t sit on a chair made with the same approach. I’m working class, you see, so I believe in, and love, skill and craft. Which takes time to achieve. Just like an anarchist society.

LH: Would you consider ever moving back into a commune?

CH: Now that is an interesting question. Anytime before now, if you had asked me that I would have answered with a hollow, cynical laugh, ‘Ha, Ha’ but considering it now, for the first time in some years, I’m surprised to say that, “Yes, I would”. I must have a think about this.

LH: How is the new edition of the graphic guide going? When are you planning on releasing it?

CH: Slowly. I was two-thirds finished, would’ve delivered it to AK Press by summer 2006 then I had a fucking heart attack. So it’ll get published when it gets published. It is absolutely brilliant, and it will change the world. I’ve just got to finish it, that’s all.

More information on Clifford Harper can be found at his website: www.agraphia.uk.com

Anarchist portraits - Clifford Harper

Spanish War

"Dig This" - Clifford Harper. Linoleum cut. Cover art for the 1985 benefit album, "Dig This: A Tribute to the Great Strike".

Clifford Harper

casino capitalism

"Country Diary Drawings" By Clifford Harper (published by Agraphia Press, London 2003)

Illustration by Clifford Harper/Agraphia.co.uk

"A

Little History Of The World" By E.H. Gombrich, Illustrations By

Clifford Harper (YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS New Haven And London 2008

illo-by-clifford-harper

leninism

anarchy and An Alphabet

anarchy and An Alphabet

San Michele Aveva un gallo Θανάσης Παπακωνσταντίνου Clifford ...

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XoA7CBwrMkI

09 dic 2012 - Caricato da Etin Arcadiaego

Ο ελάχιστος εαυτός,Θανάσης Παπακωνσταντίνου 2010 llustrator, Clifford Harper San Michele aveva un gallo, film by Paolo and Vittorio ...

Immagini correlate:

Le immagini potrebbero essere soggette a copyright.Invia feedback

Le immagini potrebbero essere soggette a copyright.Invia feedback

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento